"Not everybody can just be passive. You can't basically free ride on a well-functioning market. Somebody needs to vote."

-Nicolai Tangen, Norway's $1.5 trillion Government Pension Fund Global (quoted in the WSJ)

John Vogle's legacy is complete.

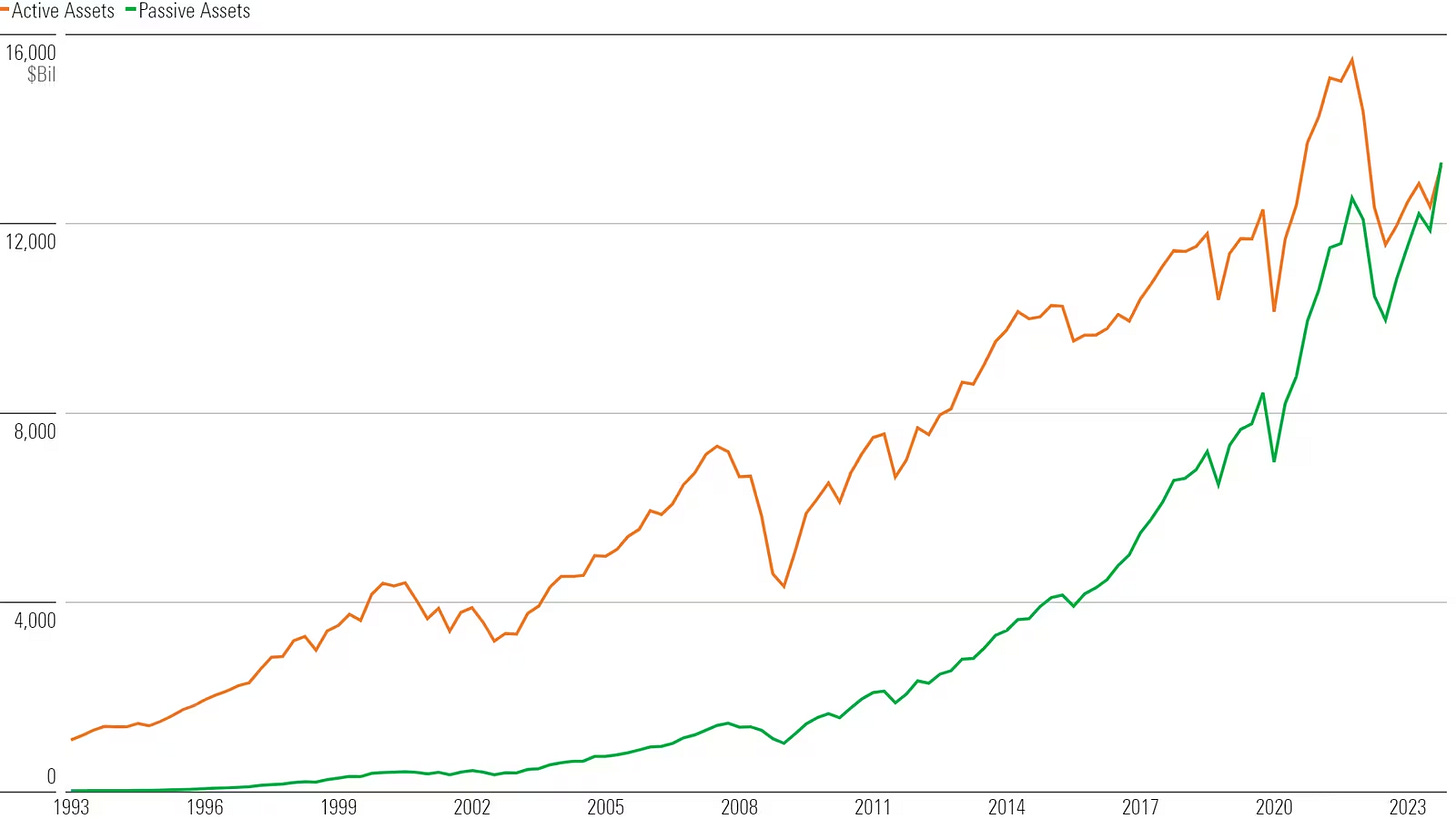

In 2023, total investments in passive funds eclipsed their actively managed counterparts for the first time. Vogle has been a famous advocate for passive investing, just holding the entire market and not trying to pick individual winners, since he founded Vanguard in 1974.

His theory is undoubtedly sound and backed by evidence, and it has served most investors well—saving us from our instinct to trade too actively, buying high and selling low in most cases.

Most of us are not Warren Buffets, including so-called professionals.

On the other hand, this growing passivity is also great news for poorly run companies and lazy and corrupt management teams. Passive investors buy the whole market, rarely vote, and never sell; therefore, they never exercise their voice to influence poorly run companies - whether criminal or merely incompetent.

Certainly, it is fair to look at the chart above and think this is an exaggerated thought. After all, half of all investments and trillions of dollars are still held by actively managed funds.

But the trend is clear and accelerating.

As this chart shows, it has taken twenty years of net outflows from active funds to reach this tipping point, but it will continue to accelerate.

Cartoon Capitalism

I was already well down this wormhole when I saw this article in the WSJ this week:

+Why We Risk a Cartoon Version of Capitalism - WSJ

The article acknowledges that active investors still engage with the companies they own to keep them on the right track.

However, the article also points out that:

"…the situation (with passive investing) is bad enough to make the biggest equity investor in the world worry that the passive approach that dominates its own strategy risks damaging markets. It's getting more active as a result."

Being an active investor takes time, energy, money, and staff. As passive funds fight to have the lowest expense ratio, there's no budget for those things. But if everyone is passive, who votes?

"Not everybody can just be passive," said Nicolai Tangen, who runs Norway's $1.5 trillion oil fund, the Government Pension Fund Global. "You can't basically free ride on a well-functioning market. Somebody needs to vote."

So, with passive funds taking over and ESG beating a hasty retreat, who's stepping up and holding companies accountable? The article above argues that it is mainly done by large, long-term shareholders, such as pensions and university endowments.

However, as we saw with ESG and university presidents losing their jobs over reactions to political events, these groups can be subject to political forces.

G is for Governance, or Death to ESG!

For all of its faults, the death of ESG (at least in the U.S.) will bring a huge sigh of relief to corporate boards worldwide.

Investor activism due to the growth of these funds has been trending higher. Contrary to what politicians made a huge stink about and what grabbed the most headlines, corporate governance issues represent the vast majority of ESG-related activism campaigns, far outweighing environmental or social issues.

Remember those Japanese companies Warren Buffett invested in that we discussed last week? In the recent Berkshire shareholder letter, Buffett highlighted some qualities in these Japanese companies that he found attractive beyond their market position or stock valuations.

He stated:

In certain important ways, all five companies – Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui and Sumitomo – follow shareholder-friendly policies that are much superior to those customarily practiced in the U.S. Since we began our Japanese purchases, each of the five has reduced the number of its outstanding shares at attractive prices.

Meanwhile, the managements of all five companies have been far less aggressive about their own compensation than is typical in the United States.

It sure sounds like the Oracle of Omaha takes governance into account.

ESG is active investing, but its flaws left it open to political criticism. Attempting to reflect environmental, social, and governance issues (a staple of corporate oversight and active investing) in one simple score paved the way for dismissing all of these themes at once.

Active Investing in the Ocean 100

If you recall the Japanese component of the Ocean 100 last week, there was undoubtedly a standout in the group. I'm not talking about Namura Shipbuilding just because it returned 1200%. (Ok, there are two standouts.)

I'm talking about the laggard, OUG Holdings.

OUG posted a negative return over the period while and the overall Japanese market was up over 50% and the portfolio was up over 200%.

Here's the list of companies and their returns to refresh your memory.

A passive investor (and most of us) would look at this and say, "Up 240%, awesome!" However, this approach fails to consider the individuals and holds outliers to any sort of accountability for their performance.

As Nicolai Tangen, manager of Norway's $1.5 trillion Government Pension Fund Global, points out, OUG is getting a free ride.

Encouraging Participation in Benchmarking

A while back, I wrote about a relatively new group called the World Benchmarking Alliance and how its benchmarks should become more relevant and important in the wake of ESG's decline.

Their more targeted benchmarks - such as the Seafood Stewardship or Transport benchmarks - offer better comparison tools than the broadly defined, murky, and gameable ESG scores.

To see how things stacked up, I thought I would see if there was any overlap between performance and the companies benchmarked by the WBA Sustainable Seafood Benchmark (OUG Holdings is a seafood company).

At this point, the WBA has benchmarked 14 of the Ocean 100 companies. Six of the 24 seafood companies in the Ocean 100 are ranked within the Seafood Stewardship benchmark, so clearly, it is a limited subset at this point.

However, what stands out is OUG's ranking in the index - #29 out of 30, with a score of 0.0.

Interesting.

Looking at the WBA page on OUG, it states that,

OUG Holdings' performance in the 2023 Seafood Stewardship Index is poor compared to its peers in the seafood industry. Compared to 2021, the company's rank in the benchmark has not changed.

The company can significantly improve its reporting in the areas of governance and strategy, environment, traceability and social responsibility. OUG Holdings can significantly improve its performance in the four measurement areas by disclosing information on its sustainable activities in English.

Thai Union, on the other hand, is ranked number one in the benchmark and is described as:

...distinguishing itself from its peers by its efforts to ensure decent working and living conditions on board fishing vessels, whilst monitoring for compliance and providing evidence of improvements.

Thai Union is also the third-best performing company in the governance and strategy, and traceability measurement areas. The company demonstrates its traceability efforts with a consistent and thorough disclosure on the Ocean Disclosure Project, where it provides a full overview of the source of its seafood products.

You can see the full Seafood Stewardship Benchmark ranking here.

Ok, so OUG is being punished for not publishing data in English. You just don't know about their actual sustainability efforts from this source. It would be time to dig deeper if you think these activities are linked. (If you care, if you have the time/personnel to do it.)

One thing is clear. There is room to question its performance and whether management is being held to account.

Our Oceans Need Active Investors

Sustainable ocean investors care about the environmental, social, and governance issues that ESG embodies. We care about the oceans.

However, the motivations for engaging with a company and representing shareholder interest can be selfish and apolitical from a fiduciary standpoint.

As Tangen further states in that WSJ article:

"We do not consider ourselves a global policeman," he says. "We do not operate as a public-sector entity. We're hopefully shrewd capitalist investors. Everything we do we do to enhance future long-term returns."

An unhealthy ocean is bad for the seafood business and many other industries. Closed fishing seasons and limited catch quotas dent profits and add volatility and risk to doing business in the sector.

A supply chain rife with human rights abusers risks customers seeking alternatives.

Why is a company like OUG Holdings lagging its peers and the market so significantly? Why are their sustainability efforts, if they exist, not published in English? What are a company's risks to supply chain audits or investigative reports revealing its business practices?

We can’t just leave it to journalists like Ian Urbina to ask these questions. Investors, those with skin in the game, need to stay involved.

Related Reading

If you’re a newer subscriber and are interested in active funds in the blue economy you might be interested in these previous posts:

It's good that you highlight this. The problem is likely to get worse unfortunately. The percentage of total AUM in active mutual funds dropped to 46% as of September 2021, but if the current trend continues it will drop to 17% by 2035, and the active management industry will disappear altogether by 2050. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4539706