The Improvers - Ocean Investing Part II

From companies to countries, identifying the improvers can lead to better returns.

I’ve had informative and inspiring calls with private investors over the last few weeks. Still, my mind was still in the public investing wormhole on the heels of last week’s article on the new KSEA Ocean Engagement ETF. Instead of moving on to the next thing, I couldn’t help sticking around this theme as I sat pecking away on my keyboard, dozens of tabs open.

So here I am for another round to understand active equity ownership, the cumulative impact of small nudges, and the issue of divesting vs. engaging with those pesky, dirty corporations one might call “The Laggards.”

Research into Rockefeller Asset Management’s (RAM) strategy behind the new KSEA ETF revealed that you can break down companies into three main groups regarding their operation’s effect on the oceans - Leaders, Improvers, and Laggards.

Further, RAM identifies that there is too much focus on the Leaders. Leaders would be those companies whose businesses are naturally, in this case, ocean-positive. A leader could also be a company that is already significantly addressing their environmental footprint.

Investing in these companies and calling yourself green (or blue) is easy. These are the companies that an exclusionary strategy can safely invest in without explaining themselves.

However, engagement with the “improvers” to move up the scale can lead to outsized financial returns and environmental impact. This group in the middle is the company that needs to evolve and is open to change but might not know how to go about it.

They want to do better.

As the prospectus of the KSEA ETF notes:

Ocean Improvers: companies whose activities are currently having a negative to neutral impact on oceans or ocean resources but who are taking, or have formally expressed to the Sub-Adviser they are considering taking, material steps towards enhancing sustainability initiatives and reducing the impact that their products or services have on oceans or ocean resources over time, in conjunction with the Sub-Adviser’s preliminary engagement objectives.

The Fund anticipates that a majority of the Fund’s assets will be invested in Ocean Improvers (emphasis mine).

What interests me is the clear line you can draw from the “ocean improvers” of the new ETF up to the very top of Rockefeller’s management. This connection leads me to believe their commitment to this strategy goes beyond current trends in ESG or Oceans.

It won’t blow around with the wind and is backed by empirical data.

From National Improvers to Ocean Improvers

The current chair of Rockefeller International is economist and emerging market investor Ruchir Sharma.

I’m a huge fan of Sharma’s books, which are based on his research and hands-on experience from over 20 years as Morgan Stanley’s Head of Emerging Markets and Chief Global Strategist. I’m always on the lookout for his contributions to the Financial Times.

(Honestly, I didn’t even have to stage this photo. That book was already sitting on my window sill.)

Sharma has written three books on the subject of identifying emerging markets with the qualities needed to generate outsized returns:

Breakout Nations (2012)

The Rise and Fall of Nations (2017)

The 10 Rules of Successful Nations (2020)

At a high level, these books focus on identifying improvers in the global economy. While he calls them “breakout nations,” in this context, he may have called them “improver nations.”

The books outline specific rules for identifying these improvers. Some of these rules fit your general macro datasets - population growth, debt-to-GDP ratios, government and consumer spending - but others are more unique.

These include rules on “second cities” (central city should only outsize second city by 3:1) and “good vs. bad billionaires” (total billionaire wealth approx 10% of GDP; inherited share approx 35% is normal; what industries create the wealth (tech vs unproductive commodities and real estate).

There are also rules around politicians, specifically around newly elected leaders.

Countries, like companies, need to change and evolve. But they don’t want to. The more entrenched interests are, the less they want to give up their gravy trains.

But as Sharma states,

“Successful nations rally around a reformer.”

And the evidence around how much change happens in the first months of a new reformist administration versus a more established one is stark.

“Since 1988, major emerging countries have held 100 elections producing 76 new leaders. Markets outperformed the global average for emerging markets by 16% in the first term. They barely matched the global average in the second term.”

[Note: this quote is from my notes taken while reading The 10 Rules of Successful Nations and might not match the exact wording.]

Other stats include:

Of leaders who lasted five years, the market outperformed the average by 20% in the first 43 months

80% of that gain coming in the first 24 months

After 43 months, the market started moving sideways

A derivative rule of this data:

Beware the leader who abolishes term limits.

So, how is this any different from identifying improver companies?

Companies That Don’t Change Disappear

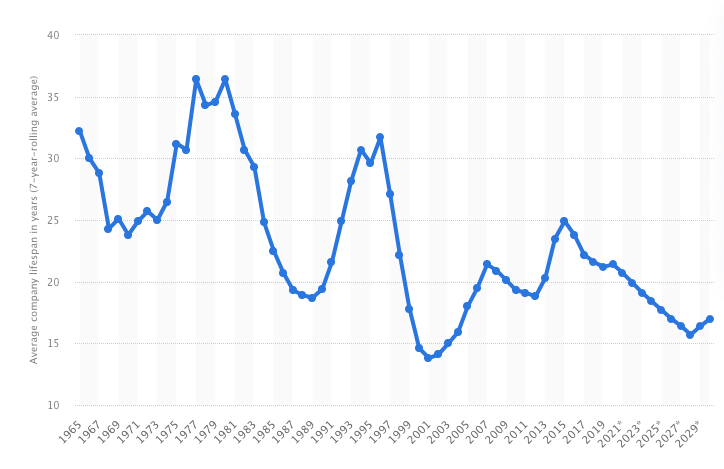

Change is the only constant in our global economy. The average life of a company in the SP500 has fallen to below 20 years.

Source: Statista

However, as change management guru Carlton Christensen continually pointed out, companies aren’t that good at change.

“Executives whose companies are currently making lots of money ought not to wonder whether the power to earn attractive profits will shift, but when.”

+Skate to where the money will be - HBR

Cool Resource: The Essential Clayton Christensen Articles

Identifying The Improvers

This week, market intelligence firm Kroll released The ESG and Global Investor Returns Study (Sept 2023). This study is one of the most comprehensive to date that delves into whether companies with high ESG scores outperform their peers.

What they found was that:

“Globally, ESG Leaders earned an average annual return of 12.9%, compared to an average 8.6% annual return earned by Laggard companies. This represents an approximately 50% premium in terms of relative performance by top-rated ESG companies.”

While the Kroll report compares leaders and laggards across geographies and markets, Rockefeller takes it a step further around this idea of improvers.

+ESG Improvers - RAM

+ESG Improvers: An Alpha Enhancing Factor (2020) - RAM

This research resulted in the Rockefeller ESG Improvers Score (REIS), “a score that ranks a company’s improvement in performance on material ESG issues relative to industry peers.”

According to the report:

A “hypothetical portfolio of top quintile ESG Improvers outperformed bottom quintile ESG “Decliners” by 3.8% annualized in an analysis covering US all cap equities from 2010 – 2020. The signal is monotonic, in that outperformance grew with each quintile.”

Of course, the Rockefeller Ocean Strategy, as I learned from last week’s article, dates back further than that (to around 2011).

Now, just mentioning ESG will trigger some of you (Martin, breathe. I love you, man!). So just relax for a moment and hear me out.

ESG investing in this context simply considers risks and opportunities that may arise from various environmental, social, or governance trends. Investors consider all kinds of risks and opportunities as part of their decision-making process. ESG factors are another facet of that evaluation process for some asset managers.

Identifying the improvers is much like Benjamin Graham finding undervalued companies. These are the ones, like an emerging nation, starting to pull the pieces necessary for becoming a better company in place - starting with a management team ready to take on the difficult task of reform.

Laggards Gonna Lag

It’s no surprise to any investor that those companies lagging behind their peers will be a tough case. It’s one thing for a company to have some unlocked value that needs a new leader to realize or some hidden asset that perhaps another company can acquire and maximize.

It’s another thing to be a company that doesn’t want to change.

When it comes to the Kroll ESG report, or indeed RAM’s case studies, there are laggards on sustainability issues that don’t want to change. For this particular theme, these companies are uninvestable or must be divested if that is considered a material risk to future performance.

The ESG haters will look at this and shout, “Aha!”

Yes, there will undoubtedly be some cash cows that ESG funds won’t touch, like an oil and gas production company with no other business line and no interest in diversifying (not that it should, necessarily).

And to be fair, the Kroll report points out that companies in energy and healthcare tend to be ESG laggards that still outperform.

But that’s fine; it’s just not for this particular investor.

But honestly, when it comes to an ultra-competitive, dynamic global economy where the rate of change is accelerating exponentially, who has time to be with a laggard?